Henry

Pynor was born in Ascot Vale on 1 August 1901 (not 1902, as reported in

some sources). He was the sixth child (and third son) of

Samuel Pynor (1863-1942), a prolific builder and architect who was

also active in municipal affairs and served as Mayor of Essendon in 1916-17.

A serial widower, Samuel Pynor married no fewer than three times:

firstly to Emma Lind (1862-1891), then to Lydia Cathie (1874-1905) and

finally to Alice Marie Russell (1883-1937). Henry Pynor – the

second child of Samuel's second wife – thus had a large family, with

four half-siblings between eleven and fifteen years his

senior.

Electing to follow in his father's footsteps, the young Henry Pynor enrolled in the three-year Diploma of Architecture course at the University of Melbourne, which he completed between 1918 and 1920. The following year, Pynor joined the Melbourne architectural office of Walter & Marion Griffin on the recommendation of a close friend from university, J F W "Fred" Ballantyne (1900-1988), who had become articled to the Griffins in 1919. In her memoirs, Mrs Griffin described Pynor as "one of the Australian youths who early joined our office", referring to an influx of new staff that included not only Fred Ballantyne but also Eric Nicholls (1902-1966) and Louise Lightfoot (1902-1979). While thus employed, Pynor took evening classes at the University of Melbourne Architectural Atelier, where, inevitably, the Griffin influence emerged. In one reminiscence, Pynor recalled an atelier project for a city bank, which he designed "in the Griffin-cum-Wright-cum-Sullivan manner". As he put it: "this effort of mine was marked lowest on the basis that it represents 'an attempt at the so-called Chicago style'. All my efforts to get a fuller criticism met with no success, and I shook the dust of the Atelier from my feet". So, while he passed his first year examinations in January 1922, Pynor never returned to the Atelier. Interestingly, his fellow students that year included Rupert Latimer (1899-1967), who was also associated with Griffin's Melbourne office at that time, as a draftsman with Peck & Kemter.

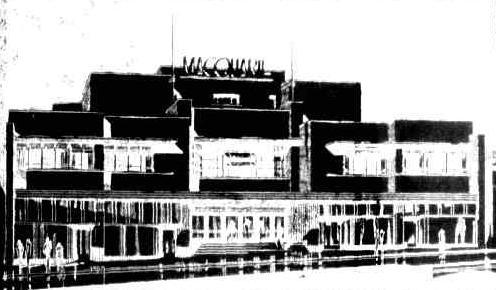

Little is otherwise known of Henry Pynor's time in the Griffin office. During 1924, he and Eric Nicholls prepared a perspective drawing for an ambitious proposal for a Civic Centre to be built over Melbourne's Jolimont railway yards, which was published in the Argus. Pynor is also known to have spent some time in Griffin's Sydney office, working on the Castlecrag development. Like other senior members of Griffin's staff, Pynor was permitted the right to private practice as long as profits were shared within the office. In this capacity, he designed houses for two of his half-siblings: one in Moonee Ponds for his half-sister Daisy (who became Mrs Frederick White in 1916) and another in St Kilda for his half-brother Archibald (since demolished).

On 19 June 1924, Henry Pynor left Sydney aboard the RMS Tahiti. Although the ship was bound for San Francisco, the passenger manifest records that Pynor's ultimate destination was London. Another young Australian architect, Austin Bramwell Smith, was also on board that same ship – and, as he also gave his ultimate destination as London, it is possible that the two men were travelling together. Arriving in the United States, Pynor spent almost two years working in architectural offices in various cities. By January 1925, he was in Chicago where, as he later recalled, "I had the pleasure of working in the office of Mundie & Jensen". This firm, descended from the late nineteenth century practice of skyscraper pioneer William Le Barron Jenney, was (as Pynor himself pointed out) best known as designers of the first fireproof steel-framed building in the world – the Home Insurance building in Chicago (1884), which, sadly, was demolished only a few years after Pynor saw in 1925.

While in Chicago, Henry Pynor also met up with his former employers Walter and Marion Griffin, who were visiting their home town after more than a decade in Australia. In a letter to a friend dated 5 January 1925, Griffin described Pynor as "our right hand man from Melbourne, who came across from Australia for experience and whatever assistance he could afford us here in odd jobs". Although the Griffins returned to Australia in late February, they arranged for Pynor to supervise the construction of a house that they had designed almost twenty years earlier for a site in Monroe, Louisiana. By January 1926, Pynor had arrived in Monroe and, by July, had sent the Griffins a photograph of the completed dwelling. During his North American tour of 1924-26, Henry Pynor is also said to have worked for the Griffin's old boss, Frank Lloyd Wright, and reportedly brought back a "valuable collection of Wright drawings". This, however, is yet to be verified. While Pynor later wrote an article on Wright for a Sydney architectural journal, the text makes no mention of actually meeting the man himself whilst in the United States.

Following his original intent, Pynor travelled on to London, although little is known of his activities there. He did spend some time on the Continent, where, as he later recalled, he observed "the straight-lined buildings that bespeak the new Architecture" in Germany and the Netherlands. Pynor also visited the Bauhaus at Dessau and, after his return to Sydney, wrote a brief article in which he outlined the school's design philosophies and illustrated examples of its work – surely one of the earliest serious responses to the International Style to be published in Australia.

After his return to Australia in 1928, Pynor spent the two years "gaining experience in Sydney offices". He is credited with involvement in the design of several new theatres, namely the State Theatre in Market Street (Henry White, with John Eberson, 1929) and the Plaza Theatre in Pitt Street (Eric F Heath, 1930). In July 1929, Pynor successfully passed the examination for registration as an architect in NSW. Around the same time, he was one of several designers (along with Roi de Maistre, Thea Proctor, Adrian Feint and Leon Gallert) who designed modern interiors as part of an exhibition of period furniture at Burdekin House. Also during 1929, Pynor married Joyce Vivian Taylor (born 1904), a local girl of Irish descent, with a talent for writing.

On 1 May 1930, Pynor and his new wife left Sydney aboard the RMMS Aorangi, bound for Canada. Travelling via Honolulu, they arrived in Vancouver three weeks later. Little is know of the Pynors professional activities in Canada, although they are is known to have spent time in Montreal, where Mrs Pynor secured some employment with her writing skills. The couple travelled thence to the United States, where, in New York City, Pynor obtained a senior position in the architectural office of York & Sawyer – a firm founded in 1898 by two proteges of McKim, Mead & White, and carried on their tradition of Beaux Arts Classicism into the 1930s. The Pynors moved thence to Great Britain, where Pynor (along with a fellow Australian, Oscar Bayne) became part of "an amazing team of politically and architecturally radical colonials and Scottish Americans" assembled by architect Francis Lorne (1889-1963) to form the mainstay of his reformed architectural practice. Pynor duly rose to the position of senior associate in the firm of Burnett, Tait & Lorne. Amongst the projects on which his is known to have worked at that time were townhouses for several prominent members of the British aristocracy, including Lord Camrose, Lord Stanley and Lord Dudley.

In early 1932, as Pynor recalled in a published memoir, "my wife and I had been rusticating in a small Hampshire village for some months when I received an invitation to join a group of Americans proceeding to Moscow to act as architectural consultants to an organisation dealing with the layout of industrial projects if the All State Building Projecting Trust – in Russian, Gosproyekstroy". The couple left London and travelled via Leningrad to Moscow, where they remained for a year. While Pynor worked on industrial development projects on the Ural mineral field (which he described in considerable detail in a later journal article), his wife Joyce gained a position on the staff of the Moscow News, the city's leading English-language daily newspaper.

By February 1933, the Pynors had returned to London, where their daughter, Valya (a Russian name, meaning "healthy and strong") was born the following year. On 27 September 1935, after spending five years travelling and working across North America, Europe, Russia and Great Britain, the Pynors departed London aboard the Orion, bound for Australia. News of their incipient arrival was reported in several newspapers around the country, which further noted that Pynor intended to return to his home town of Melbourne and commence his own architectural practice there.

By November 1935, the Pynors were back in Sydney, where they visited Marion Griffin. Her husband Walter had recently left the country, bound for India – indeed, as she herself had noted, his voyage almost overlapped with the Pynors in Perth as they returned from London. In a letter to Walter, dated 13 November, Marion reported that "Pynor turned up at the office yesterday with his wife and two-year-old daughter. He is planning to go to Melbourne in a few days. [Eric] Nicholls thinks the pseudo-boom of six months has dwindled to practically nothing. However Pynor hopes to get started through his father's clientele." Pynor, however, never made it to Melbourne. Instead, he accepted the irresistible offer of a partnership with the firm of Herbert & Wilson, founded in 1927 by two Sydney architects who, like Pynor himself, had travelled and worked extensively through Europe and the United States. Re-badged as Herbert, Wilson & Pynor, the firm subsequently won acclaim in several design competitions, including one for the new MLC Building in Sydney (1936), which won them a £100 premium, and another for the so-called "Australian Homes for Australian Forests" (1938), which won them first prize and 50 guineas. The practice otherwise undertook a range of residential, commercial and other commissions, mostly in suburbs on Sydney's North Shore, where Pynor himself lived in a modest bungalow-style house at 12 Sydney Street, Willoughby - not far from the Griffins' Castlecrag Estate, on which the young architect had worked 15 years earlier.

Not surprisingly, given the extent of their overseas travel, the Pynors became minor celebrities in the late 1930s, and were much in demand to speak and write of their adventures. In February 1936, Pynor outlined his Russian experiences in an article for the Sydney Mail, titled "I work in Russia: The Personal Experiences of a Professional Man". Four months later, on 10 June, Pynor gave a talk on Sydney radio station 2GL entitled "Working as an architect in Russia". Over the next few weeks, Pynor's talk was re-broadcast (under the title "An Australian works for the Soviets in Moscow") on several interstate radio stations including 4QB in Brisbane and 5CK in Adelaide. In the months that followed, Joyce Pynor outlined her own overseas experiences in a series of radio talks, including one titled "Adventures with a typewriter: Earning dollars in Montreal." (22 July) and another called "On the staff of the Moscow News" (5 Aug). Mrs Pynor evidently continued to do this for over a year, as she gave another radio talk, titled "Living in Russia, 1934" [sic] in September 1937. She also also wrote an interesting article for the Australian Women's Weekly, which described the increasing popularity of steel prefabricated dwellings in Europe and the United States. During this active period, her interest in writing culminated in the publication of a book on the history of the Blue Mountains, which also appeared in 1936 under the title Romantic Yesterdays. Pynor himself continued to give talks and write articles, including yet another describing his Russian experiences (May 1937) and one on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright (June 1938). This public profile culminated in Pynor's appointment to the jury for the state's prestigious architectural prize, the annual Sulman Award, on which he served in 1938, 1939, 1940 and again in 1943.

During the Second World War, Henry Pynor worked in the Procurement Division of the US Army Corps of Engineers, where, as Philip Goad and Julie Willis have noted, he worked on the design of a portable parachute drying flue. Also employed in the division at that time was Pynor's old university friend (and former Griffin colleague), Fred Ballantyne, whom he had not seen for two decades. After the War, rather than returning to private practice, Pynor accepted a senior teaching position at the Sydney Technical College. Amongst numerous other initiatives, Pynor was responsible for bringing in a new generation of teaching staff, including Morton Herman (1907-83), who taught Mechanics and Design and later became an eminent architectural historian. During this period, Pynor otherwise remained prominent in the profession. In April 1945, advantage was taken of his pre-war expertise in theatre design when he was invited to speak at a conference to formalise plans for a National Theatre.

Henry Pynor died on 7 June 1946 (not 1945, as has been incorrectly cited in some sources) in Sydney's North Shore Hospital, following a short illness. At the time of his death, he was Lecturer-in-Charge at the Sydney Technical College, an Associate-elect of the Royal Institute of British Architects, a Fellow of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, and the Vice-President of its NSW Chapter. Sadly, his personal life was rather less successful; his marriage was evidently in trouble at the time of his death and, even two months later, the case of "H Pynor vs J V Pynor" was still scheduled to be heard in the Divorce Court. Notwithstanding, as an obituary noted, "his work with the Chapter and in his short tenure of the Technical College will exercise a lasting influence on matters architectural".

Electing to follow in his father's footsteps, the young Henry Pynor enrolled in the three-year Diploma of Architecture course at the University of Melbourne, which he completed between 1918 and 1920. The following year, Pynor joined the Melbourne architectural office of Walter & Marion Griffin on the recommendation of a close friend from university, J F W "Fred" Ballantyne (1900-1988), who had become articled to the Griffins in 1919. In her memoirs, Mrs Griffin described Pynor as "one of the Australian youths who early joined our office", referring to an influx of new staff that included not only Fred Ballantyne but also Eric Nicholls (1902-1966) and Louise Lightfoot (1902-1979). While thus employed, Pynor took evening classes at the University of Melbourne Architectural Atelier, where, inevitably, the Griffin influence emerged. In one reminiscence, Pynor recalled an atelier project for a city bank, which he designed "in the Griffin-cum-Wright-cum-Sullivan manner". As he put it: "this effort of mine was marked lowest on the basis that it represents 'an attempt at the so-called Chicago style'. All my efforts to get a fuller criticism met with no success, and I shook the dust of the Atelier from my feet". So, while he passed his first year examinations in January 1922, Pynor never returned to the Atelier. Interestingly, his fellow students that year included Rupert Latimer (1899-1967), who was also associated with Griffin's Melbourne office at that time, as a draftsman with Peck & Kemter.

Little is otherwise known of Henry Pynor's time in the Griffin office. During 1924, he and Eric Nicholls prepared a perspective drawing for an ambitious proposal for a Civic Centre to be built over Melbourne's Jolimont railway yards, which was published in the Argus. Pynor is also known to have spent some time in Griffin's Sydney office, working on the Castlecrag development. Like other senior members of Griffin's staff, Pynor was permitted the right to private practice as long as profits were shared within the office. In this capacity, he designed houses for two of his half-siblings: one in Moonee Ponds for his half-sister Daisy (who became Mrs Frederick White in 1916) and another in St Kilda for his half-brother Archibald (since demolished).

On 19 June 1924, Henry Pynor left Sydney aboard the RMS Tahiti. Although the ship was bound for San Francisco, the passenger manifest records that Pynor's ultimate destination was London. Another young Australian architect, Austin Bramwell Smith, was also on board that same ship – and, as he also gave his ultimate destination as London, it is possible that the two men were travelling together. Arriving in the United States, Pynor spent almost two years working in architectural offices in various cities. By January 1925, he was in Chicago where, as he later recalled, "I had the pleasure of working in the office of Mundie & Jensen". This firm, descended from the late nineteenth century practice of skyscraper pioneer William Le Barron Jenney, was (as Pynor himself pointed out) best known as designers of the first fireproof steel-framed building in the world – the Home Insurance building in Chicago (1884), which, sadly, was demolished only a few years after Pynor saw in 1925.

While in Chicago, Henry Pynor also met up with his former employers Walter and Marion Griffin, who were visiting their home town after more than a decade in Australia. In a letter to a friend dated 5 January 1925, Griffin described Pynor as "our right hand man from Melbourne, who came across from Australia for experience and whatever assistance he could afford us here in odd jobs". Although the Griffins returned to Australia in late February, they arranged for Pynor to supervise the construction of a house that they had designed almost twenty years earlier for a site in Monroe, Louisiana. By January 1926, Pynor had arrived in Monroe and, by July, had sent the Griffins a photograph of the completed dwelling. During his North American tour of 1924-26, Henry Pynor is also said to have worked for the Griffin's old boss, Frank Lloyd Wright, and reportedly brought back a "valuable collection of Wright drawings". This, however, is yet to be verified. While Pynor later wrote an article on Wright for a Sydney architectural journal, the text makes no mention of actually meeting the man himself whilst in the United States.

Following his original intent, Pynor travelled on to London, although little is known of his activities there. He did spend some time on the Continent, where, as he later recalled, he observed "the straight-lined buildings that bespeak the new Architecture" in Germany and the Netherlands. Pynor also visited the Bauhaus at Dessau and, after his return to Sydney, wrote a brief article in which he outlined the school's design philosophies and illustrated examples of its work – surely one of the earliest serious responses to the International Style to be published in Australia.

After his return to Australia in 1928, Pynor spent the two years "gaining experience in Sydney offices". He is credited with involvement in the design of several new theatres, namely the State Theatre in Market Street (Henry White, with John Eberson, 1929) and the Plaza Theatre in Pitt Street (Eric F Heath, 1930). In July 1929, Pynor successfully passed the examination for registration as an architect in NSW. Around the same time, he was one of several designers (along with Roi de Maistre, Thea Proctor, Adrian Feint and Leon Gallert) who designed modern interiors as part of an exhibition of period furniture at Burdekin House. Also during 1929, Pynor married Joyce Vivian Taylor (born 1904), a local girl of Irish descent, with a talent for writing.

On 1 May 1930, Pynor and his new wife left Sydney aboard the RMMS Aorangi, bound for Canada. Travelling via Honolulu, they arrived in Vancouver three weeks later. Little is know of the Pynors professional activities in Canada, although they are is known to have spent time in Montreal, where Mrs Pynor secured some employment with her writing skills. The couple travelled thence to the United States, where, in New York City, Pynor obtained a senior position in the architectural office of York & Sawyer – a firm founded in 1898 by two proteges of McKim, Mead & White, and carried on their tradition of Beaux Arts Classicism into the 1930s. The Pynors moved thence to Great Britain, where Pynor (along with a fellow Australian, Oscar Bayne) became part of "an amazing team of politically and architecturally radical colonials and Scottish Americans" assembled by architect Francis Lorne (1889-1963) to form the mainstay of his reformed architectural practice. Pynor duly rose to the position of senior associate in the firm of Burnett, Tait & Lorne. Amongst the projects on which his is known to have worked at that time were townhouses for several prominent members of the British aristocracy, including Lord Camrose, Lord Stanley and Lord Dudley.

In early 1932, as Pynor recalled in a published memoir, "my wife and I had been rusticating in a small Hampshire village for some months when I received an invitation to join a group of Americans proceeding to Moscow to act as architectural consultants to an organisation dealing with the layout of industrial projects if the All State Building Projecting Trust – in Russian, Gosproyekstroy". The couple left London and travelled via Leningrad to Moscow, where they remained for a year. While Pynor worked on industrial development projects on the Ural mineral field (which he described in considerable detail in a later journal article), his wife Joyce gained a position on the staff of the Moscow News, the city's leading English-language daily newspaper.

By February 1933, the Pynors had returned to London, where their daughter, Valya (a Russian name, meaning "healthy and strong") was born the following year. On 27 September 1935, after spending five years travelling and working across North America, Europe, Russia and Great Britain, the Pynors departed London aboard the Orion, bound for Australia. News of their incipient arrival was reported in several newspapers around the country, which further noted that Pynor intended to return to his home town of Melbourne and commence his own architectural practice there.

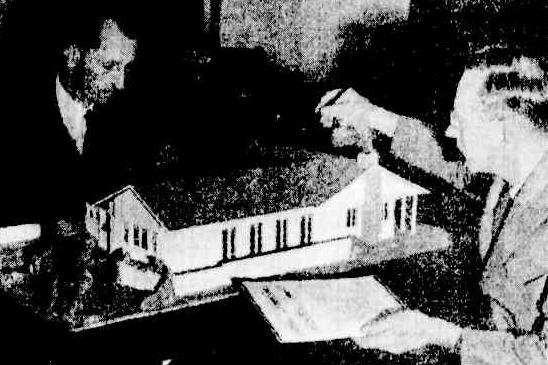

By November 1935, the Pynors were back in Sydney, where they visited Marion Griffin. Her husband Walter had recently left the country, bound for India – indeed, as she herself had noted, his voyage almost overlapped with the Pynors in Perth as they returned from London. In a letter to Walter, dated 13 November, Marion reported that "Pynor turned up at the office yesterday with his wife and two-year-old daughter. He is planning to go to Melbourne in a few days. [Eric] Nicholls thinks the pseudo-boom of six months has dwindled to practically nothing. However Pynor hopes to get started through his father's clientele." Pynor, however, never made it to Melbourne. Instead, he accepted the irresistible offer of a partnership with the firm of Herbert & Wilson, founded in 1927 by two Sydney architects who, like Pynor himself, had travelled and worked extensively through Europe and the United States. Re-badged as Herbert, Wilson & Pynor, the firm subsequently won acclaim in several design competitions, including one for the new MLC Building in Sydney (1936), which won them a £100 premium, and another for the so-called "Australian Homes for Australian Forests" (1938), which won them first prize and 50 guineas. The practice otherwise undertook a range of residential, commercial and other commissions, mostly in suburbs on Sydney's North Shore, where Pynor himself lived in a modest bungalow-style house at 12 Sydney Street, Willoughby - not far from the Griffins' Castlecrag Estate, on which the young architect had worked 15 years earlier.

Not surprisingly, given the extent of their overseas travel, the Pynors became minor celebrities in the late 1930s, and were much in demand to speak and write of their adventures. In February 1936, Pynor outlined his Russian experiences in an article for the Sydney Mail, titled "I work in Russia: The Personal Experiences of a Professional Man". Four months later, on 10 June, Pynor gave a talk on Sydney radio station 2GL entitled "Working as an architect in Russia". Over the next few weeks, Pynor's talk was re-broadcast (under the title "An Australian works for the Soviets in Moscow") on several interstate radio stations including 4QB in Brisbane and 5CK in Adelaide. In the months that followed, Joyce Pynor outlined her own overseas experiences in a series of radio talks, including one titled "Adventures with a typewriter: Earning dollars in Montreal." (22 July) and another called "On the staff of the Moscow News" (5 Aug). Mrs Pynor evidently continued to do this for over a year, as she gave another radio talk, titled "Living in Russia, 1934" [sic] in September 1937. She also also wrote an interesting article for the Australian Women's Weekly, which described the increasing popularity of steel prefabricated dwellings in Europe and the United States. During this active period, her interest in writing culminated in the publication of a book on the history of the Blue Mountains, which also appeared in 1936 under the title Romantic Yesterdays. Pynor himself continued to give talks and write articles, including yet another describing his Russian experiences (May 1937) and one on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright (June 1938). This public profile culminated in Pynor's appointment to the jury for the state's prestigious architectural prize, the annual Sulman Award, on which he served in 1938, 1939, 1940 and again in 1943.

During the Second World War, Henry Pynor worked in the Procurement Division of the US Army Corps of Engineers, where, as Philip Goad and Julie Willis have noted, he worked on the design of a portable parachute drying flue. Also employed in the division at that time was Pynor's old university friend (and former Griffin colleague), Fred Ballantyne, whom he had not seen for two decades. After the War, rather than returning to private practice, Pynor accepted a senior teaching position at the Sydney Technical College. Amongst numerous other initiatives, Pynor was responsible for bringing in a new generation of teaching staff, including Morton Herman (1907-83), who taught Mechanics and Design and later became an eminent architectural historian. During this period, Pynor otherwise remained prominent in the profession. In April 1945, advantage was taken of his pre-war expertise in theatre design when he was invited to speak at a conference to formalise plans for a National Theatre.

Henry Pynor died on 7 June 1946 (not 1945, as has been incorrectly cited in some sources) in Sydney's North Shore Hospital, following a short illness. At the time of his death, he was Lecturer-in-Charge at the Sydney Technical College, an Associate-elect of the Royal Institute of British Architects, a Fellow of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, and the Vice-President of its NSW Chapter. Sadly, his personal life was rather less successful; his marriage was evidently in trouble at the time of his death and, even two months later, the case of "H Pynor vs J V Pynor" was still scheduled to be heard in the Divorce Court. Notwithstanding, as an obituary noted, "his work with the Chapter and in his short tenure of the Technical College will exercise a lasting influence on matters architectural".

Select List of Projects

Henry Pynor (Victoria)

| 1923 | Residence for F W White, 5 Ophir Street, Moonee Ponds Residence for A H Pynor, 38 Marine Parade, St Kilda [demolished] |

Herbert, Wilson & Pynor (NSW)

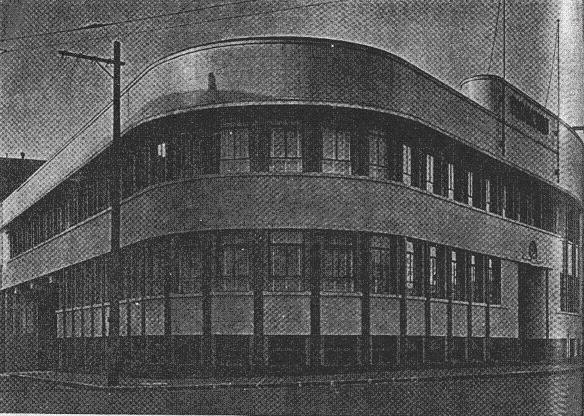

| 1936 1937 1938 1938 1939 1939 1939 1939 1940 1940 1940 1940 1941 1941 | Office building for MLC Assurance Company, Martin Place, Sydney [competition entry] Alterations to St Mark's Rectory, Springdale Road, Killara Design for "Australian Homes for Australian Forests" [competition entry] Picture Theatre for H Taylor (of the Macquarie Stud Farm), Wellington Conversion of residence into flats, 104 Kurraba Road, Neutral Bay Additions to residence, Livingstone Avenue, Pymble Residence, Hopetoun Avenue, Mosman Weatherboard cottage, Northwood Sports Pavilion, Mosman Oval, Mosman (in association with Alfred Hale, council architect) Refacing of office building (Yaralla House), 109 Pitt Street, Sydney Council chambers for Municipality of Mosman (in association with Alfred Hale) Brick residence, Woollahra Residence for P D Felton, St John's Avenue, Gordon Office building for Paramount Film Service Pty Ltd, 53-55 Brisbane Street, Surry Hills |

| |

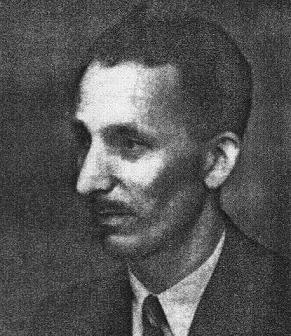

| Henry Pynor, circa 1937 |

| |

| Detail of Henry Pynor and Eric Nicholls' perspective for a Civic Centre over Melbourne's Jolimont Railwayds (1924) |

| |

| Scheme for a modern picture theatre at Wellington, NSW (Herbert, Wilson & Pynor, 1938) |

| |

| Henry Pynor

(left) and E D Wilson, of Herbert, Wilson & Pynor, with a model of

their prize-winning entry in the "Australian Homes for Australian

Forests" competition |

| |

| Administrative offices for Paramount Film Service Pty Ltd, Surry Hills, NSW (Herbert, Wilson & Pynor, 1941) |

| Select References Henry Pynor, "A Brief Note on the Aims and Ideals of the Bauhaus", The Home, 1 October 1928, pp 48-49. Vivian Pynor, "Steel Walls a Modern Home do make", Australian Women's Weekly, 7 March 1936, p 3. Henry Pynor, "An Architectural Foreign Specialist in Russia", Architecture, 1 May 1937, pp 96-101. "Henry Pynor, ARAIA", Decoration & Glass, February 1938, pp 53-54 Henry Pynor, "Some Aspects of the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright", Architecture, 1 June 1938, pp 136-139 "The Late Henry Pynor", Architecture, Jan-Mar 1947, p 279 (note: page wrongly dated as Jan-Mar 1946) Marion Griffin, "The Magic of America" (unpublished typescript, ca 1949), Vol 1, p 35. Donald Leslie Johnson, Australian Architecture 1901-1951: Sources of Modernism (1980), pp 111-112. Paul Kruty, "The Gilbert Cooley House, 1925: Walter Burley Griffin's last American Building", Fabrications, Vol 6 (June 1995), p 16. Andrew Metcalf, Architecture in Transition: The Sulman Awatrd, 1932-1996 (1997), pp 69-72, 75. Philip Goad & Julie Willis, "Invention from War: A circumstantial modernism for Australian architecture", in James Madge & Andrew Peckham (eds), Narrating Architecture: A Respective Anthology (2006), p 318. Dictionary of Scottish Architects, 1840 to 1980, www.scottisharchitects.org.uk, sv Francis Lorne. Special thanks to Pynor's great-nephew, Greg Stahel, and Melbourne architect John Kenny, for sharing their research. |